Posting this at half time. Whichever way the match ends, I’ll take this as a Hornsey Road endorsement:

THE HORNSEY ROAD

Not Abbey Road.

Sunday, 11 July 2021

Friday, 9 October 2020

You leave a neighbourhood and this happens.

https://www.theguardian.com/food/2020/oct/09/big-jo-london-n7-a-bit-of-genius-grace-dent-restaurant-review

Sunday, 13 September 2020

Chewing Gum

Watching this years after I should have and my the Andover is beautiful. Post-Covid we ought to redirect the tourists stuck outside Buckingham Palace and show them the main Andover square instead.

Wednesday, 13 November 2019

Zeppelins painted by a POW.

| Imperial War Museum: © IWM (EPH 1882) |

I've tried to write this post so many times, but have never been able to do it justice. In the spirit of not letting the best be the enemy of the good, here goes.

In the Imperial War Museum, there's a painting showing Islington being hit by Zeppelin bombs. It's by a German in the PoW camp in what had been the Islington Workhouse on Cornwallis Road. Between 1915 and 1919 there were 600-700 German civilians there. It was a specialist camp, where POWs made brushes and prosthetic limbs and were allowed weekly visits from relatives.

The caption says 'Workhouse. Lest I forget. Islington. September 2 - Nov. 1916. 'Lest I forget' is a remembrance phrase, but this is before Remembrance Day. The leaves are oak leaves. Oaks seem to be a national symbol in Germany, but the Royal Navy claims the oak too.

I haven't been able to find out the artists' name. I can't believe he could have been an amateur - too good, but also too polished. This looks like a commercial artists' work.

Why he painted it, God knows. I couldn't tell you why I wrote this blog, or why after years away I'm rounding up loose ends.

I'll leave you with what a proper historian said about WW1 prisoners in London. If you still want more, follow the Manchester University Press link for Panikos Panayi's book.

Jerry White wrote 'The Germans, for instance, were long-established in both the East End and West End, with suburban communities at all points of the London compass. Charlotte Street, west of Tottenham Court Road, was the main West-End artery, known as “Charlottenstrasse” and famous for its restaurants and clubs. In the rest of London there were a dozen German churches, a Salvation Army German Corps, a German Hospital, two German-language newspapers, a great German Gymnasium at King’s Cross, and associations for every interest-group from amateur theatricals to chess-players, cyclists to military men. German merchants and traders, stockbrokers and bankers, had carved out an important niche in the City; the German governess had become a necessity in many upper-class homes; and the German waiter among proletarian migrants, and bakers and barbers among tradesmen, had become what seemed like irreplaceable fixtures in London’s economic life. With their high rates of intermarriage with English women and their readiness to stay in London rather than return “home”, no foreign community was more integrated than the Germans. August 1914 would change all that.

The war began a process of eradication of German influence from London life, an influence honourably exerted over many generations that had given much to metropolitan culture. Everywhere German-born Londoners were thrown out of work, from lowly German waiters to Theodore Kroell, popular manager of the Ritz in Piccadilly since 1909, to Prince Louis of Battenburg, First Sea Lord, forced out of the Admiralty by the press, jealous enemies and “a stream of letters, signed and anonymous”, calling for his dismissal. German surnames became anglicised or abandoned: the orchestral conductor Basil Cameron changed his name from Hindenberg, the Merton-born writer Ford Hermann Hueffer became Ford Madox Ford, and the House of Commons was assured there were no clerks employed in the Treasury of German or Austrian nationality: “One British-born clerk, who had a name of Teutonic origin, has changed it since the outbreak of War” .

8There were adjustments everywhere. In the Reform Club, as in the rest of clubland, notices were posted asking members not to bring alien enemies as guests. In Sainsbury’s, “German sausage”, a big favourite with the Londoners prewar, was quickly renamed “Luncheon sausage”. In Bermondsey, where “We were not without a large share of aliens in our midst”, shop fascias were transformed from “Schnitzler, et cetera” to “The Albion Saloon”, or “The British Barbers of Bermondsey”. The study of German was abandoned at Toynbee Hall, the university settlement in Whitechapel. Pubs changed their names, so that the King of Prussia, formerly popular in London, now became a rarity (one in Tooley Street became the King of Belgium); and local residents across the metropolis campaigned for the Teutonic taint to be removed from their street names often, after much delay, with success – Stoke Newington’s Wiesbaden Road becoming Belgrade Road, for instance.

9All this was productive of much misery. Among the large number of prosecutions of Germans for failing to register was a trickle of press reports from September 1914 of the suicide of Londoners who overnight had become enemy aliens: Joseph Pottsmeyer, 52, a gramophone packer from Hoxton, sacked from his job and unable to get another, found hanged in his room alongside a note expressing admiration for England; John Pfeiffer, assistant manager at the Holborn Viaduct Hotel, who shot himself in the eye and then, with extraordinary determination, the temple; and four weeks later an Austrian couple, recently married and only in their twenties, who took poison “it is believed… from fear of internment and separation.” There would be many others.

10In addition, sporadic violence against German shopkeepers in the poorer trading streets of London began immediately after the declaration of war. Before 1914 was out it turned much worse. That October saw the first serious outbreak of collective violence by the Londoners, beginning at Deptford and widely copied in other parts of south London for a few nights after. The crowds of 5,000 or so were so fierce and persistent that the police had to call out the military for assistance – butchers’ and bakers’ shops were wrecked and looted, shopkeepers and their families fleeing to friendly English neighbours for protection. These alarming riots had been triggered locally by the arrival in south London of Belgian refugees fleeing from the fall of Antwerp and arriving in London with little more than the clothes they stood up in.[7]See PANAYI P., “Anti-German Riots in Britain during the Fir

11Worse was to come. On the afternoon of Friday 7 May 1915 the great Cunard liner RMS Lusitania was torpedoed off Queenstown, Ireland, with the loss of 1,198 lives, including many women and children and 124 US citizens. The sinking shocked and horrified the world. The news reached London with the evening papers. It was received as a culmination of atrocities, the horrors of the German invasion of Belgium widely aired in the British press. Over the weekend of 8 and 9 May serious anti-German rioting broke out in Liverpool, the Lusitania’s home port. Then, beginning in Canning Town, West Ham, and other parts of east London on 11 May, and building to a London-wide conflagration on Wednesday the 12th, a frenzy of violence fell upon Germans in London. Over the next six days, every Metropolitan Police division from Harrow to Croydon and Hayes to Romford experienced violent disturbances. At least 257 people were injured, including 107 police officers, regular and special, beaten for standing between the Germans and the crowd. There were 866 arrests. By great good fortune no one was killed. Shops thought to be run by Germans or Austrians had windows smashed and doors broken down. Interiors – staircases, cupboards, ceilings – were ‘hacked to pieces’. Provisions and property were carted away by the barrowful. The looting and violence extended to homes as well as shops.

12This would prove the worst outbreak of violence against the Germans in London, though sporadic outbreaks followed many air raids later in the war. But official action against them through the internment of men, including men well beyond fighting age, and the repatriation to Holland of thousands of German men, women and children continued throughout the war. The results were plainly apparent. In 1911 the census had recorded 31,254 Germanborn residents of the county of London, excluding all or most of the outer suburbs; in 1921 the number had fallen to 9,083. The comparable figures for Austrians were 8,869 and 1,552.'[8]SMITH Sir H.L. (ed.), The New Survey of London Life and Labour

Sources:

https://coinsweekly.com/german-oaks-and-national-sentiments/

http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/30081898

https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/prisoners_of_war_and_internees_great_britain

https://manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk/9780719078347/

https://www.cairn.info/revue-cahiers-bruxellois-2014-1E-page-139.html

https://reviews.history.ac.uk/review/1455

Tuesday, 5 November 2019

'Oh well, I suppose it's not the place's fault,' I said. 'Nothing, like something, happens anywhere.'

Hornsey Road was so unlucky to miss out. Would have changed the geography of London had the Beatles recorded there. https://t.co/mwNoUqVKOi

— Mark Lewisohn (@marklewisohn) October 6, 2019

Monday, 4 November 2019

In 1874 he bet £300 that he could ride a penny farthing from Bath to London in one day

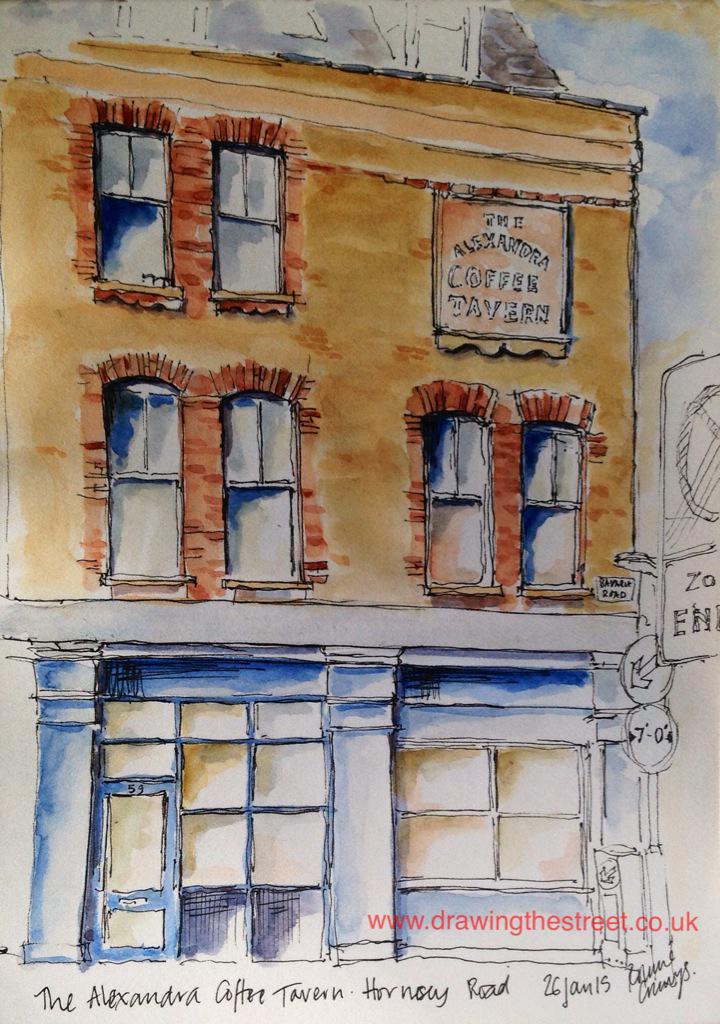

Here's the Alexandra Coffee House by Ronnie Cruwys of drawingthestreet.com

The sign is misleading. This was the Blenheim Arms public house for far longer than it was the Alexandra Coffee House - and the road was Blenheim Road before it became Bavaria Road.

The sign is misleading. This was the Blenheim Arms public house for far longer than it was the Alexandra Coffee House - and the road was Blenheim Road before it became Bavaria Road.

I've trawled through local newspapers, court records and anything else I could think of and found nothing about the Alexandra. It came, was worthy, and vanished.

The Blenheim Arms, on the other hand, had a great man for a landlord.

In the 1870s David Stanton managed the pub and invented endurance cycling at the same time. And I don't mean the solitary disappear off into the distance kind, I mean a swashbuckling, extravagant, race against horses kind of endurance. The Guardian has the story here: https://www.theguardian.com/sport/ng-interactive/2015/oct/24/london-six-day-race-cycling-inside-track

And here’s more:

In 1874 he bet £300 that he could ride a penny farthing from Bath to London in one day. He lost by only 54 minutes after he 'was attacked four miles from Colnbrook by four men, who hurled heavy clubs at him. One struck him over the right eye and knocked him off the bicycle, another broke the middle wheel of the machine. Although partially stunned, he managed to walk as far as Colnbrook. There he mounted anothe rmachine belonging to a Mr Percy, and reached the goal at High Street Kensington at 3.54 pm, losing the match by fifty four minutes. He left Bath at 7 am and before the above mentioned outrage was committed he had been delayed twenty minutes by being run into by a cart. On his arrival at Kensington, Mr Stanton was, it is said, bleeding, bruised and covered in mud.'

In the 1870s David Stanton managed the pub and invented endurance cycling at the same time. And I don't mean the solitary disappear off into the distance kind, I mean a swashbuckling, extravagant, race against horses kind of endurance. The Guardian has the story here: https://www.theguardian.com/sport/ng-interactive/2015/oct/24/london-six-day-race-cycling-inside-track

And here’s more:

In 1874 he bet £300 that he could ride a penny farthing from Bath to London in one day. He lost by only 54 minutes after he 'was attacked four miles from Colnbrook by four men, who hurled heavy clubs at him. One struck him over the right eye and knocked him off the bicycle, another broke the middle wheel of the machine. Although partially stunned, he managed to walk as far as Colnbrook. There he mounted anothe rmachine belonging to a Mr Percy, and reached the goal at High Street Kensington at 3.54 pm, losing the match by fifty four minutes. He left Bath at 7 am and before the above mentioned outrage was committed he had been delayed twenty minutes by being run into by a cart. On his arrival at Kensington, Mr Stanton was, it is said, bleeding, bruised and covered in mud.'

[Pall Mall Gazette - Monday 21 September 1874]

Later that same year he appeared at 'Cremorne Gardens’ as a competitor with Arthur Markham in a race of 50 miles,

‘the latter receiving a quarter of an hour's start. In passing the bend of smallest radius Markham certainly showed himself the steadier rider and better tactician of the two, as he never failed to gain a yard or more from his antagonist by close shaving. But here all superiority of Markham over Stanton ceases.

The former was very soon deprived of his fifteen minutes' advantage and many times in quick succession was caught and passed by his dashing rival. Before half the distance had been covered Stanton was five miles ahead. He rode a larger machine than that selected by Markham, and made the great size of the leading wheel conducive to extraordinary speed. Twice or thrice Markham was seized with violent cramps, and no one could doubt the severity of his suffering each time he was compelled to dismount.

Stanton, though slightly deficient in steadiness at times, has a very pretty style, throwing his body forward, with his head and shoulders back, and keeping his chest well expanded. His seat is remarkably easy, and the action of his legs as mechanically regular as the coupling-rods of a locomotive.

In the commencement of his 35th mile Markham unwillingly gave in, not before cries of 'Turn it up Arthur, it's no use' had been raised by the more considerate of his friends and supportes. Once, when he was off his bicycle, having his legs chafed to restore the suppleness of the muscles, racked by rheumatism, he resisted all entreaties to abandon the contest, saying in answer to every persuasive argument, 'He' - that was to say Stanton - 'might fall'.

In the meantime, Stanton was proceeding coolly enough, though at great pace, and was declining offers of weak brandy and water in favour of 'a cup o' tea'. He had throughout the race done as he liked with Markham, now waiting on him as a cat ready for the spring waits on a crippled mouse, now riding jauntily by his side, and now shooting to the front with his hands placed carelessly on his hips instead of the handles of his machine.' [Sheffield Daily Telegraph - Wednesday 14 October 1874]

By 1875 he was 'the 100 mile champion, whose previous performances over long distance have made his reputation as a stayer unequalled', [London Standard - Wednesday 27 October 1875]

In 1877, at the Edinburgh Agricultural Hall, he beat six trotting horses by two and a half laps over 100 miles. [Edinburgh Evening News - Monday 26 February 1877]

Later that same year he appeared at 'Cremorne Gardens’ as a competitor with Arthur Markham in a race of 50 miles,

‘the latter receiving a quarter of an hour's start. In passing the bend of smallest radius Markham certainly showed himself the steadier rider and better tactician of the two, as he never failed to gain a yard or more from his antagonist by close shaving. But here all superiority of Markham over Stanton ceases.

The former was very soon deprived of his fifteen minutes' advantage and many times in quick succession was caught and passed by his dashing rival. Before half the distance had been covered Stanton was five miles ahead. He rode a larger machine than that selected by Markham, and made the great size of the leading wheel conducive to extraordinary speed. Twice or thrice Markham was seized with violent cramps, and no one could doubt the severity of his suffering each time he was compelled to dismount.

Stanton, though slightly deficient in steadiness at times, has a very pretty style, throwing his body forward, with his head and shoulders back, and keeping his chest well expanded. His seat is remarkably easy, and the action of his legs as mechanically regular as the coupling-rods of a locomotive.

In the commencement of his 35th mile Markham unwillingly gave in, not before cries of 'Turn it up Arthur, it's no use' had been raised by the more considerate of his friends and supportes. Once, when he was off his bicycle, having his legs chafed to restore the suppleness of the muscles, racked by rheumatism, he resisted all entreaties to abandon the contest, saying in answer to every persuasive argument, 'He' - that was to say Stanton - 'might fall'.

In the meantime, Stanton was proceeding coolly enough, though at great pace, and was declining offers of weak brandy and water in favour of 'a cup o' tea'. He had throughout the race done as he liked with Markham, now waiting on him as a cat ready for the spring waits on a crippled mouse, now riding jauntily by his side, and now shooting to the front with his hands placed carelessly on his hips instead of the handles of his machine.' [Sheffield Daily Telegraph - Wednesday 14 October 1874]

By 1875 he was 'the 100 mile champion, whose previous performances over long distance have made his reputation as a stayer unequalled', [London Standard - Wednesday 27 October 1875]

In 1877, at the Edinburgh Agricultural Hall, he beat six trotting horses by two and a half laps over 100 miles. [Edinburgh Evening News - Monday 26 February 1877]

Friday, 20 November 2015

Albemarle Mansions Part Two: Bessie Butt

@RonnieCruwys has started adding colour to the Albemarle Mansions and that means I can tell you about Bessie Butt.

'Music Hall Divorce: Principal 'Boy's' Farewell Letter to Her Husband:

Mr Alfred Earl Sydney Davis, a music hall agent and author, obtained a divorce in Sir Samuel Evans' Court from his wife (who is known on the stage as Bessie Butt, and who stated to be earning £600 a year) on the gound of her miscondunt with Mr. David Pool, also a music hall artiste. The case was not defended, and the jury fixed the damages at £250 against the correspondent, a sum agreed upon between the parties. Married in 1901, the parties lived happily together till February last, when Mr Davis received a letter from his wife from Glasgow, where she was performing the principal boy's part in 'Aladdin' saying that she had left him for ever. Mrs Davis was afterwards discovered living at Albemarle Mansions, Holloway, with correspondent, whom she had met in 1903, when staying with her husband in rooms in Kennington Park Road.' - 25 June 1910, Dundee Courier

'Dave Poole, the ventriloquist and Bessie Butt, the male impersonator, were quietly married at Liverpool March 18.' - 4 April 1911, Variety

She could have done better. Ventriloquist. Pah.

As principal boy in Aladdin, pantomime, Theatre Royal, Glasgow, Christmas 1909. There's more here. |

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)